For engineers building high-concurrency applications in e-commerce, fintech or media, the “200ms limit” is a hard ceiling. It is the psychological threshold where interaction feels instantaneous. If a personalized homepage, search result or “Up Next” queue takes longer than 200 milliseconds to load, user abandonment spikes. There is a famous study from Amazon showing that every 100ms of latency cost them 1% in sales. In the streaming world, that latency translates directly to “churn.”

The problem is that the business always wants smarter, heavier models. They want large language models (LLMs) to generate summaries, deep neural networks to predict churn and complex reinforcement learning agents to optimize pricing. All of these push latency budgets to the breaking point.

As an engineering leader, I often find myself acting as the mediator between data science teams who want to deploy massive parameters and site reliability engineers (SREs) who are watching the p99 latency graphs turn red.

To reconcile the demand for better AI with the reality of sub-second response times, we must rethink our architecture. We need to move away from monolithic request-response patterns and decouple inference from retrieval.

Here is a blueprint for architecting real-time systems that scale without sacrificing speed.

The architecture of the two-pass system

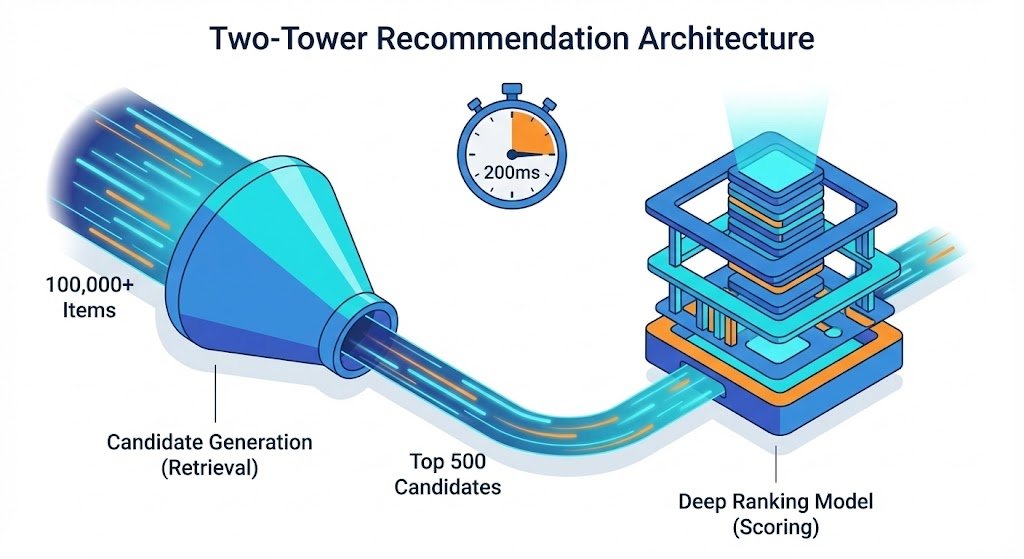

A common mistake I see in early-stage personalization teams is trying to rank every item in the catalog in real-time. If you have 100,000 items (movies, products or songs), running a complex scoring model against all 100,000 for every user request is mathematically impossible within 200ms.

Manoj Yerrasani

To solve this, we implement a two-tower architecture (or a candidate generation and ranking split).

- Candidate generation (the retrieval layer): This is a fast, lightweight sweep. We use vector search or simple collaborative filtering to narrow the 100,000 items down to the top 500 candidates. This step prioritizes recall over precision. It needs to happen in under 20ms.

- Ranking (the scoring layer): This is where the heavy AI lives. We take those 500 candidates and run them through the sophisticated deep learning model (e.g. XGBoost or a neural network) that considers hundreds of features like user context, time of day and device type.

By splitting the process, we only spend our expensive compute budget on the items that actually have a chance of being shown. This funnel approach is the only way to balance scale with sophistication.

Solving the cold start problem

The first hurdle every developer faces is the “cold start.” How do you personalize for a user with no history or an anonymous session?

Traditional collaborative filtering fails here because it relies on a sparse matrix of past interactions. If a user just landed on your site for the first time, that matrix is empty.

To solve this within a 200ms budget, you cannot afford to query a massive data warehouse to look for demographic clusters. You need a strategy based on session vectors.

We treat the user’s current session (clicks, hovers and search terms) as a real-time stream. We deploy a lightweight Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) or a simple Transformer model right at the edge or in the inference service.

As the user clicks “Item A,” the model immediately infers a vector based on that single interaction and queries a Vector Database for “nearest neighbor” items. This allows us to pivot the personalization in real-time. If they click a horror movie, the homepage reshuffles to show thrillers instantly.

The trick to keeping this fast is to use hierarchical navigable small world (HNSW) graphs for indexing. Unlike a brute-force search which compares the user vector against every item vector, HNSW navigates a graph structure to find the closest matches with logarithmic complexity. This brings query times down from hundreds of milliseconds to single-digit milliseconds.

Crucially, we only compute the delta of the current session. We do not re-aggregate the user’s lifetime history. This keeps the inference payload small and the lookup instant.

The decision matrix: Inference vs. pre-compute

Another architectural flaw I frequently encounter is the dogmatic attempt to run everything in real-time. This is a recipe for cloud bill bankruptcy and latency spikes.

You need a strict decision matrix to decide exactly what happens when the user hits “load.” We divide our strategy based on the “Head” and “Tail” of the distribution.

First, look at your head content. For the top 20% of active users or globally trending items (e.g. the Super Bowl stream or a viral sneaker drop), you should pre-compute recommendations. If you have a VIP user who visits daily, run those heavy models in batch mode via Airflow or Spark every hour.

Store the results in a low-latency Key-Value store like Redis, DynamoDB or Cassandra. When the request comes in, it is a simple O(1) fetch that takes microseconds, not milliseconds.

Second, use just-in-time inference for the tail. For niche interests or new users that pre-computing cannot cover, route the request to a real-time inference service.

Finally, optimize aggressively with model quantization. In a research lab, data scientists train models using 32-bit floating-point precision (FP32). In production, you rarely need that level of granularity for a recommendation ranking.

We compress our models to 8-bit integers (INT8) or even 4-bit using techniques like post-training quantization. This reduces the model size by 4x and significantly reduces memory bandwidth usage on the GPU. Often, the accuracy drop is negligible (less than 0.5%), but the inference speed doubles. This is often the difference between staying under the 200ms ceiling or breaking it.

Resilience and the ‘circuit breaker’

Speed means nothing if the system breaks. In a distributed system, a 200ms timeout is a contract you make with the frontend. If your sophisticated AI model hangs and takes 2 seconds to return, the frontend spins and the user leaves.

We implement strict circuit breakers and degraded modes.

We set a hard timeout on the inference service (e.g., 150ms). If the model fails to return a result within that window, the circuit breaker trips. We do not show an error page. Instead, we fall back to a “safe” default: a cached list of “Popular Now” or “Trending” items.

From the user’s perspective, the page loaded instantly. They might see a slightly less personalized list, but the application remained responsive. Better to serve a generic recommendation fast than a perfect recommendation slow.

Data contracts as a reliability layer

In a high-velocity environment, upstream data schemas change constantly. A developer adds a field to the user object or changes a timestamp format from milliseconds to nanoseconds. Suddenly, your personalization pipeline crashes because of a type mismatch.

To prevent this, you must implement data contracts at the ingestion layer.

Think of a data contract as an API spec for your data streams. It enforces schema validation before the data ever enters the pipeline. We use Protobuf or Avro schemas to define exactly what the data should look like.

If a producer sends bad data, the contract rejects it at the gate (putting it into a dead letter queue) rather than poisoning the personalization model. This ensures that your runtime inference engine is always fed clean, predictable features. It prevents the “garbage in, garbage out” scenarios that cause silent failures in production.

Observability beyond the average

Finally, how do you measure success? Most teams look at “average latency.” This is a vanity metric. It hides the experience of your most important users.

Averages smooth over the outliers. But in personalization systems, the outliers are often your “power users.” The user with 5 years of watch history requires more data processing than a user with 5 minutes of history. If your system is slow only for heavy data payloads, you are specifically punishing your most loyal customers.

We look strictly at p99 and p99.9 latency. This tells us how the system performs for the slowest 1% or 0.1% of requests. If our p99 is under 200ms, then we know the system is healthy.

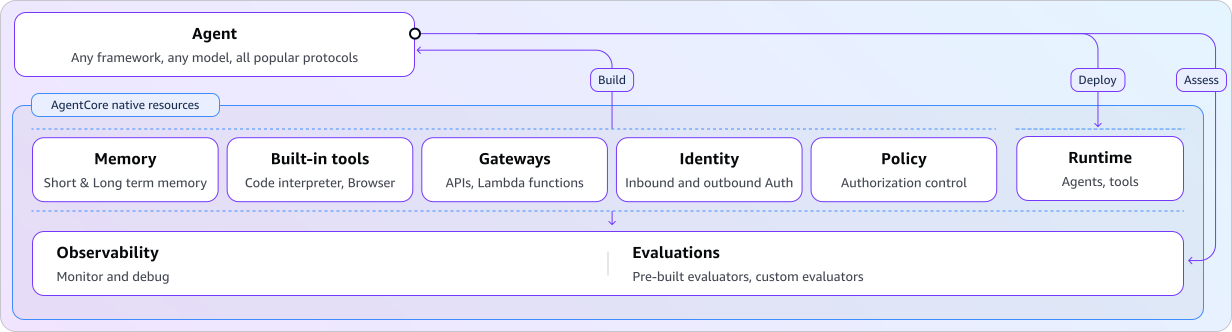

The architecture of the future

We are moving away from static, rule-based systems toward agentic architectures. In this new model, the system does not just recommend a static list of items. It actively constructs a user interface based on intent.

This shift makes the 200ms limit even harder to hit. It requires a fundamental rethink of our data infrastructure. We must move compute closer to the user via edge AI, embrace vector search as a primary access pattern and rigorously optimize the unit economics of every inference.

For the modern software architect, the goal is no longer just accuracy. It is accuracy at speed. By mastering these patterns, specifically two-tower retrieval, quantization, session vectors and circuit breakers, you can build systems that do not just react to the user but anticipate them.

This article is published as part of the Foundry Expert Contributor Network.

Want to join?

Go to Source

Author: